Glucose

Physiological role and pathophysiology, reference intervals and the most likely causes of abnormalities

Glucose

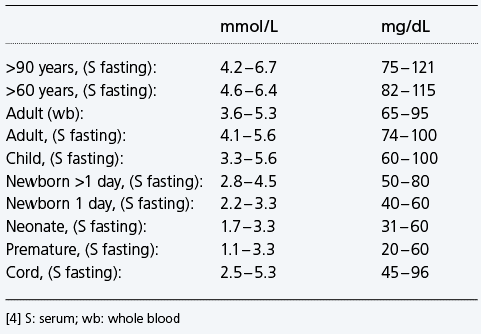

Reference interval glucose - examples

Physiological significance of glucose and blood glucose regulation

Why measure blood/plasma glucose ?

When should glucose be measured ?

Hyperglycemia and diabetes

Hyperglycemia and the critically ill patients

Causes of hyperglycemia

Symptoms of hyperglycemia

Hypoglycemia

Causes of hypoglycemia

Symptoms of hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia and neonates

Causes of hypoglycemia in neonates include

Glucose, the most abundant carbohydrate in human metabolism, serves as the major intracellular energy source (see lactate). Glucose is derived principally from dietary carbohydrate, but it is also produced – primarily in the liver and kidneys – via the anabolic process of gluconeogenesis, and from the breakdown of glycogen (glycogenolysis). This endogenously produced glucose helps keep blood glucose concentration within normal limits, when dietary-derived glucose is not available, e.g. between meals or during periods of starvation.

Reference interval glucose – examples

Physiological significance of glucose and blood glucose regulation

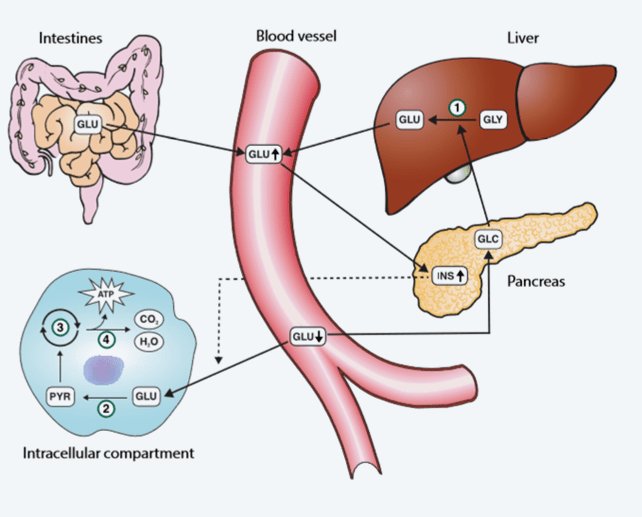

The body can only utilize glucose within cells, where it is the major source of energy. In every cell of the body this energy is released by the oxidation of glucose to carbon dioxide and water in two sequential metabolic pathways: the glycolytic pathway and the citric acid cycle. During this oxidative process the energy-rich compound adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is formed, and this, in turn, drives the multiplicity of chemical reactions required for tissue cells to remain viable and fulfill their function. Oxidation of one molecule of glucose by this process yields 36 molecules of energy-rich ATP (Fig. 15).

FIG. 15: The glucose pathway. 1: Glycogenolysis; 2: Glycolysis; 3: Citric acid cycle; 4: Oxidative phosphorylation GLU: Glucose; GLY: Glycogen; GLC: Glucagon; INS: Insulin; PYR: Pyruvate; ATP: Adenosine triphosphate

For this energy-generating function to proceed, glucose must be transported from the intestines (food) or liver (gluconeogenesis, glycogenesis) to body cells via the blood circulation, and enter the tissue cells. Glucose entry to cells from blood is dependent on insulin. This, in part, explains why hyperglycemia is a defining feature of diabetes and highlights the role of insulin in regulating blood glucose concentration. The maintenance of blood glucose concentration within normal limits is in fact dependent on two pancreatic hormones: insulin and glucagon. Insulin is secreted from the pancreas in response to rising blood glucose, and has the effect of reducing blood glucose; whereas glucagon is secreted from the pancreas in response to falling blood glucose and has the effect of increasing blood glucose. By the synergistic opposing action of these two hormones, blood glucose concentration remains within normal limits.

Insulin reduces blood glucose by:

- Enabling entry of glucose to cells from blood

- Promoting cell metabolism (oxidation) of glucose via the glycolytic pathway

- Promoting formation of glycogen from glucose in the liver and muscle cells

- Inhibiting liver/kidney production of glucose via gluconeogenesis

Glucagon increases blood glucose by:

- Promoting liver/muscle production of glucose from glycogen (glycogenolysis)

- Promoting liver/kidney production of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources (gluconeogenesis)

In situations where there is reduced carbohydrate supply from the intestines, gluconeogenesis becomes particularly important for maintaining a normal blood glucose level and thereby the supply of glucose to all tissues [151].

The non-carbohydrate substrates from which glucose is formed during gluconeogenesis include:

- Proteins

- Glycerol

- Glucose metabolism intermediaries like lactate and pyruvate [152]

Despite widely variable intervals between meals or the occasional consumption of meals with a substantial carbohydrate load, blood glucose concentration does not usually rise above around 8.0 – 9.0 mmol/L (144 – 162 mg/dL) nor fall below around 3.5 mmol/L (63 mg/dL) in healthy individuals [153]. The highest levels (8.0 – 9.0 mmol/L) occur 1 – 1.5 hours after eating carbohydrate-containing food and the lowest levels occur before food in the morning (i.e. after an overnight fast).

Why measure blood/plasma glucose?

The principal reason for measuring circulating glucose concentration is to diagnose and monitor diabetes mellitus, a very common chronic metabolic condition characterized by increased blood glucose concentration (hyperglycemia), due to an absolute or relative deficiency of the pancreatic hormone insulin [148]. The two main types of diabetes are referred to as type 1 (insulin-dependent) and type 2 (insulin-resistant). Diabetes treatment, which is aimed at normalizing blood glucose concentration, is associated with constant risk of reduced blood glucose (hypoglycemia), which can lead to impaired cerebral function, impaired cardiac performance, muscle weakness, and is associated with glycogen depletion and diminished glucose production.

Abnormality in blood glucose concentration is not confined to those with diabetes. Transient (stress-related) hyperglycemia is a common acute effect of critical illness, whatever its cause. Identification and effective treatment of hyperglycemia (i.e. normalizing blood glucose) improves the chances of surviving critical illness for both diabetic and non-diabetic patients [149].

Neonates, particularly those born prematurely, are at high risk of reduced blood glucose (hypoglycemia). According to [150] the key to prevent complications from glucose deficiency “is to identify infants at risk, promote early and frequent feedings, normalize glucose homeostasis, measure glucose concentrations early and frequently in infants at risk, and treat promptly when glucose deficiency is marked and symptomatic” [150].

When should glucose be measured?

When there are signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, suspicion of diabetes (hyperglycemia), or hyperglycemia as result of stress in critically ill patients [154].

Hyperglycemia and diabetes

In the absence of critical illness diabetes is confirmed if fasting plasma glucose is ≥7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or random plasma glucose is consistently ≥11 mmol/L (>198 mg/dL). Those with fasting plasma glucose in the range of 5.6 – 6.9 mmol/L (101 – 124 mg/dL) have fasting hyperglycemia, but it is not sufficiently severe to make the diagnosis of diabetes. The label ”impaired fasting glucose” is applied to these individuals, who are at much greater-than-normal risk of developing diabetes at some time in the future. The acute and chronic long-term complications of diabetes are avoided by normalization of blood glucose concentration using exogenous insulin and/or other blood glucose-lowering drugs. Recommended targets are for preprandial (fasting) plasma glucose to be maintained in the range of 3.9 – 7.2 mmol/L (70 – 130 mg/dL), and peak (1 – 2 hours postprandial) plasma glucose should not exceed 10.0 mmol/L (180 mg/dL) [155].

Hyperglycemia and the critically ill patients

Hyperglycemia occurs frequently, whether secondary to diabetes or stress-induced (in the non-diabetic), in the critically ill patient [156]. The body increases glucose production and can become resistant to the effects of insulin, with resulting hyperglycemia. In one study, intensive insulin therapy targeting arterial glucose levels of 4.4 – 6.1 mmol/L (79 – 110 mg/dL) in a primarily surgical ICU patient population resulted in a significant decrease on morbidity and mortality [154]. However, aggressive intensive insulin therapy can lead to hypoglycemia [157]. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) [155] recommends that in the majority of critically ill patients in the ICU, insulin infusion should be used to control hyperglycemia if blood glucose exceeds 10 mmol/L (180 mg/dL). The aim of such therapy is to maintain glucose in the range of 7.8 – 10 mmol/L (141 – 180 mg/dL). For selected patients more stringent goals, such as 6.1 – 7.8 mmol/L (110 – 141 mg/dL), may be appropriate as long as it does not lead to significant hypoglycemia. According to ADA a target <6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL) is not recommended [155].

Causes of hyperglycemia [23]

- Trauma

- Stroke/myocardial infarction

- Surgery

- Diabetes mellitus

- Acute pancreatitis

- Endocrine hyperfunction

- Hemochromatosis

- Impaired glucose tolerance/impaired fasting glucose

- Drugs

Symptoms of hyperglycemia

- Headaches

- Dehydration

- Palpitations

- Respiratory abnormalities

- Frequent urination

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Thirst

- Gastrointestinal disturbances

- Altered mental status and/or sympathetic nervous system stimulation

- Ketonemia/-uria

- Pseudohyponatremia

- Metabolic acidosis

Critically ill patients can experience rise in blood glucose concentration as a result of:

- The initial trauma

- Surgery

- Inhaled anesthesia

- Medications, particularly corticosteroids

- Intravenous solutions used for drug and fluid administration

- Dialysis solutions

- Infections, particularly sepsis

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia is defined as decreased blood glucose concentration. The glucose level at which an individual becomes symptomatic is highly variable; therefore a single blood glucose concentration that categorically defines hypoglycemia is not established [158]. In some intensive care settings hypoglycemia is defined as blood glucose <2.2 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) [156].

Causes of hypoglycemia [23]

- Diabetes treatment (most common cause)

- Insulinoma, liver disease

- Postgastrectomy

- Insulin abuse

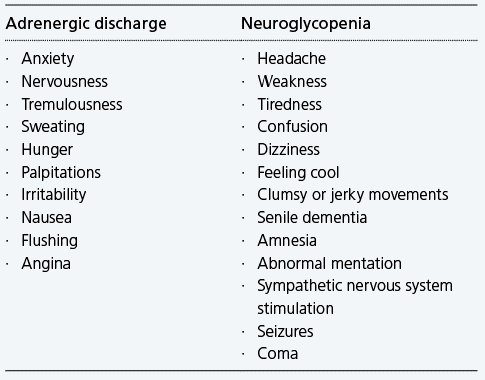

Symptoms of hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia symptoms can either result from adrenergic discharge or from neuroglycopenia.

Hypoglycemia and neonates

In neonates, hypoglycemia is a common metabolic issue. However, there is no consensus on a single blood glucose concentration that defines hypoglycemia in this population. Experts agree that the neurological disabilities associated with neonatal hypoglycemia depend on gestational and chronological age and associated risk factors such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy and that they frequently result after situations of persistent and severe hypoglycemia [159,160].

Although there is no consensus, most expert authors support the cut-off value of 2 mmol/L (36 mg/dL) for asymptomatic healthy newborns. Values down to 1.7 mmol/L (31 mg/dL) have been suggested in an otherwise healthy term infant [161]. Operational thresholds <2.2 mmol/L (<40 mg/dL) during the first 24 hours and <2.8 mmol/L (<50 mg/dL) thereafter are also suggested [162]. Many neonate units aim to maintain blood glucose levels above 2 – 3 mmol/L (26 – 54 mg/dL) and below 10 – 15 mmol/L (180 – 270 mg/dL) in low-birth-weight or sick babies [163].

Causes of hypoglycemia in neonates include [164]:

- Inappropriate changes in hormone secretion

- Inadequate substrate reserve in the form of hepatic glycogen

- Inadequate muscle stores as a source of amino acids for gluconeogenesis

- Inadequate lipid stores for the release of fatty acids

References

- Mikkelsen ME, Miltiades AN, Gaieski DF et al. Serum lactate is associated with mortality in severe sepsis independent of organ failure and stock. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 1670-77.

- Siggaard-Andersen O, Fogh-Andersen N, Gøthgen IH, Larsen VH. Oxygen status of arterial and mixed venous blood. Crit Care Med 1995; 23, 7: 1284-93.

- Wettstein R, Wilkins R. Interpretation of blood gases. In: Clinical assessment in respiratory care, 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2010.

- Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE. Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2012.

- Klaestrup E, Trydal T, Pederson J. Reference intervals and age and gender dependency for arterial blood gases and electrolytes in adults. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011; 49: 1495-1500.

- Higgins C. Why measure blood gases ? A three-part introduction for the novice. Part 1. www.acutecaretesting.org Jan 2012.

- Jones LW, Eves ND, Haykowsky M, Freedland SJ, Mackey JR. Exercise intolerance in cancer and the role of exercise therapy to reverse dysfunction. Lancet Oncol 2009; 10: 598-605.

- Higgins C. Causes and clinical significance of increased carboxyhemoglobin. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2005.

- Higgins C. Methemoglobin. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2006.

- Siggaard-Andersen O, Ulrich A, Gøthgen IH. Classes of tissue hypoxia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995; 39,107: 137-42.

- Higgins C. Why measure blood gases ? A three-part introduction for the novice. Part 3. www.acutecaretesting.org Apr 2013.

- Sola A, Rogido M, Deulofeut R. Oxygen as a neonatal health hazard: call for détente in clinical practice. Acta Paediatrica 2007; 96: 801-12.

- White A. The evaluation and management of hypoxemia in the chronic critically ill patient. Clin Chest Med 2001; 22: 123-34.

- Walshaw M, Hind C. Chest disease. In: Axford J, Callaghan CO, eds. Medicine. 2nd ed. Oxford UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004.

- Malley W. Clinical Blood gases: assessment and intervention. 2nd ed. Elsevier Saunders, 2004.

- Hennessey I, Japp A. Arterial blood gases made easy. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 2007.

- Hoffbrand AV, Moss PAH, Pettit JE. Erythropoiesis and general aspects of anaemia. In: Hoffbrand AV, Moss PAH, Pettit JE, eds. Essential haematology. 5th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2006: 12-28.

- Ranney H, Aharma V. Structure and function of haemoglobin. In: Beutler E, Lichtman MA, Coller BS, Kipps TJ, Seligsohn U, eds. William’s hematology. 6th ed. New York City: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2000: 345-53.

- Higgins C. Hemoglobin and its measurement. www.acutecaretesting.org Jul 2005.

- Mclellan SA, Walsh TS. Oxygen delivery and haemoglobin. CEACCP 2004; 4: 123-26.

- West B. Respiratory physiology: the essentials. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2012: 36-56.

- Higgins C. Parameters that reflect the carbon dioxide content of blood. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2008.

- Bakerman S. ABC’s of interpretive laboratory data. 4th ed. Scottsdale: Interpretive Laboratory Data, 2002.

- CLSI. Blood gas and pH analysis and related measurements; Approved Guidelines. CLSI document CA46-A2, 29, 8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 940 West Valley Road, Suite 1400, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087-1898 USA, 2009.

- Thomas L. Critical limits of laboratory results for urgent clinician notification. eJIFCC 2003; 14,1: 1-8. http://www.ifcc.org/ifccfiles/docs/140103200303.pdf (Accessed Aug 2013).

- Wilson B, Cowan H, Lord J. The accuracy of pulse oximetry in emergency department patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Emergency Medicine 2010; 10: 9.

- Gøthgen IH, Siggaard-Andersen O, Kokholm G. Variations in the haemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curve in 10079 arterial blood samples. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1990; 50, Suppl 203: 87-90.

- Kokholm G. Simultaneous measurements of blood pH, pCO2, pO2 and concentrations of haemoglobin and its derivates – a multicentre study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1990; 50, Suppl 203: 75-86.

- Breuer HWM, Groeben H, Breuer J, Worth H. Oxygen saturation calculation procedures: a critical analysis of six equations or the determination of oxygen saturation. Intensive Care Med 1989; 15: 385-89.

- Hess D, Elser RC, Agarwal NN. The effects on the pulmonary shunt value of using measured versus calculated hemoglobin oxygen saturation and of correcting for the presence of carboxyhemoglobin and methemoglobin. Respir Care 1984; 29: 1101-05.

- Shappell SD. Hemoglobin affinity for oxygen, 2,3-DPG, and cardiovascular disease. Cardiology Digest 1972; 9-15.

- Kosanin R, Stein ED. Measured versus calculated oxygen saturation of arterial blood: a clinical study. Bull N Y Acad Med 1978; 54: 951-55.

- O’Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Davison AG. BTS guideline for emergency oxygen use in adult patents. Thorax 2008; 63, Suppl VI: 1-68.

- Toffaletti J, Zijlstra W. Misconceptions in reporting oxygen saturation. Anesth Analg 2007; 105: S5-S9.

- Siggaard-Andersen O, Wimberley PD, Fogh-Andersen N, Gøthgen IH. Measured and derived quantities with modern pH and blood gas equipment: calculation algorithms with 54 equations. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1988; 48, Suppl 189: 7-15.

- Siggaard-Andersen O, Wimberley PD, Fogh-Andersen N, Gøthgen IH. Arterial oxygen status determined with routine pH/blood gas equipment and multi-wavelength hemoximetry: reference values, precision and accuracy. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1990; 50, Suppl 203: 57-66.

- Gutierrez J, Theodorou A. Oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption in pediatric critical care. In: Lucking SE, Maffei FA, Tamburro RF, Thomas NJ, eds. Pediatric critical care study guide: text and review. London: Springer-Verlag, 2012:19-38.

- Hameed S, Aird W, Cohn S. Oxygen delivery. Crit Care Med 2003; 31, Suppl 12: S658-S667.

- Siggaard-Andersen O, Gøthgen IH, Wimberley PD, Fogh-Andersen N. The oxygen status of the arterial blood revised: relevant oxygen parameters for monitoring the arterial oxygen availability. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1990; 50, Suppl 203: 17-28.

- Burnett R. Minimizing error in the determination of p50. Clin Chem 2002; 48: 567-70.

- Banak T. Fetal blood gas values. In: Modak RK, ed. Anesthesiology Keywords Review. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013: 212.

- Hsia C. Respiratory function of hemoglobin. New Eng J Med 1998; 338: 239-46.

- Stryer L. Biochemistry. 3th ed. New York: W.H. Freeman and company, 1988: 143-76.

- Andersen C. Critical haemoglobin thresholds in premature infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2001; 84: F146-48.

- Rumi E, Passamoniti F, Pagan L et al. Blood p50 evaluation enhances diagnostic definition of isolated erythrocytosis. J Intern Med 2009; 265: 266-74.

- Percy M, Butt M, Crotty G et al. Identification of high oxygen affinity hemoglobin variants in the investigation of patients with erythrocytosis. Hematologica 2009; 94: 1321-22.

- Steinberg M. Hemoglobins with altered oxygen affinity. In: Greer JP, Foerster J, Rodgers GM, Paraskevas F, eds. Wintrobes Clinical Hematology. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams and Wilkins, 2009.

- Morgan T. The oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve in critical illness. Critical Care and Resuscitation 1999; 1: 93-100.

- Lopez DM, Weingarten-Arams JS, Singer LP, Conway EE Jr. Relationship between arterial, mixed venous and internal jugular carboxyhemoglobin concentrations at low, medium and high concentrations in a piglet model of carbon monoxide toxicity. Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 1998-2001.

- Coburn RF, Williams WJ, Foster RE. Effect of erythrocyte destruction on carbon monoxide production in man. J Clin Invest 1964; 43: 1098-103.

- Breimer L, Mikhailidis D. Could carbon monoxide and bilirubin be friends as well as foes of the body ? Scand J Clin and Lab Invest 2010; 70: 1-5.

- Lippi G, Rastelli G, Meschi T, Borghi L, Cervellin G. Pathophysiology, clinics, diagnosis and treatment of heart involvement in carbon monoxide poisoning. Clin Biochem 2012; 45: 1278-85.

- Owens E. Endogenous carbon monoxide production in disease. Clin Biochem 2010; 43: 1183-88.

- Kao L, Nanagas K. Carbon monoxide poisoning. Emerg Clin N America 2004; 22: 985-1018.

- Shusterman D, Quninlan P, Lowengaart R, Cone J. Methylene chloride intoxication in a furniture refinisher. A comparison of exposure estimates utilizing workplace air sampling and carboxyhemoglobin measurements. J Occup Med 1990; 32: 451-54.

- Widdop B. Analysis of carbon monoxide. Ann Clin Biochem 2002; 39: 378-91.

- Hampson N. Pulse oximetery in severe carbon monoxide poisoning. Chest 1998; 114: 1036-104.

- Price DP. Methemoglon inducers. In: Goldfrank’s toxicological emergencies. 9th ed. New York City: McGraw Hill, 2011: 1698-1707.

- Kusin S, Tesar J, Hatten B et al. Severe methemoglobinemia and hemolytic anemia from aniline purchased as 2C-E, a recreational drug, on the internet – Oregon, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61: 85-88.

- Modarai B, Kapadia Y, Kerins et al. Methylene Blue: a treatment for severe methaemoglobinaemia secondary to misuse of amyl nitrite. Emerg Med J 2002; 19: 270-71.

- Saxena H, Saxena A. Acute methaemoglobinaemia due to ingestion of nitrobenzene (paint solvent). Indian J Anaesth 2010; 54: 160-62.

- Hamirani YS, Franklin W, Grifka RG, Stainback RF. Methemoglobinemia in a young man. Tex Heart Inst J 2008; 35: 76-77.

- Percy M, Lappin T. Recessive congenital methaemoglobinaemia: cytochrome b5 reductase deficiency. Br J Haem 2008; 141: 298-308.

- Kedar P, Nadkarni A, Phanasgoanker S et al. Congenital methemoglobinemia caused by Hb-MRatnagiri (β-63CAT→TAT, His→Tyr) in an Indian family. Am J Hematol 2005; 79: 168-70.

- Choi A, Sarang A. Drug induced methaemoglobinaemia following elective coronary artery bypass grafting. Anaesthesia 2007; 62: 737-40.

- Rehman H. Methemoglobinemia. West J Med 2001; 175: 193-96.

- Wolak E, Byerly F, Mason T, Cairns B. Methemoglobinemia in critically ill burned patients. Am J Crit Care 2005; 14: 104-08.

- Siggaard-Anderesen O. An acid-base chart for arterial blood with normal and pathophysiological reference areas. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1971; 27: 239-45.

- Higgins C. An introduction to acid-base balance in health and disease. www.acutecaretesting.org Jun 2004.

- Higgins C. Why measure blood gases ? A three-part introduction for the novice. Part 2. www.acutecaretesting.org Apr 2012.

- Kost GJ. Critical limits for urgent clinician notification at US medical centers. JAMA 1990; 263: 704-07.

- Morgan TJ. What is p50. www.acutecaretessting.org March 2003.

- Kellum J. Determinants of blood pH in health and disease. Critical Care 2000; 4: 6-14.

- Cohen R, Woods H. Disturbance of acid-base homeostasis. In: Warrel DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, eds. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Nageotte MP, Gilstrap LC III. Intrapartum fetal surveillance. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams JD, Lockwood CJ, Moore T, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s maternal-fetal medicine. Principles and practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009: 397.

- Gherman RB, Chauhan S, Ouzounian JG et al. Shoulder dystoria: The unpreventable obstetric emergency with empiric management guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2006, 195: 657-72.

- Moody J. UK’s National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). Caesarean section clinical guideline. London: RCOG Press, 2004.

- Tuffnell D, Haw W, Wilkinson K. How long does a fetal scalp blood sample take. Br J Obstet Gynae 2006; 113: 332-34.

- Higgins C. Clinical aspects of pleural fluid pH. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2009.

- Cousineau J, Anctil S, Carceller A, Gonthier M, Delvin EE. Neonate capillary blood gas reference values. Clin Biochem 2005; 38: 905-07.

- Marshall W, Bangert S. Hydrogen ion homeostasis and blood gases. In: Clinical chemistry. 5th ed. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2004.

- Siggaard-Andersen O. Textbook on acid-base and oxygen status of the blood. http://www.siggaard-andersen.dk/OsaTextbook.htm (Accessed May 2013).

- Gregg A, Weiner C. “Normal” umbilical arterial and venous acid-base and blood gas values. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1993, 36: 24-32.

- Soldin SJ, Wong EC, Brugnara C et al. Pediatric reference intervals. 7th ed. Washington DC: AACC Press, 2011.

- Siggaard-Andersen O. The acid-base status of blood. 4th rev ed. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1976.

- Kraut J, Madias N. Metabolic acidosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6: 274-85.

- Kellum J. Clinical review: Reunification of acid-base physiology. Critical Care 2005; 9: 500-07.

- Kofstad J. All about base excess – to BE or not to BE. www.acutecaretesting.org Jul 2003.

- Siggaard-Andersen O. The Van Slyke equation. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1977; 37: 15-20.

- Siggaard-Anderesen O. FAQ concerning the acid-base status of the blood. www.acutecaretesting.org Jul 2010.

- Kofstad J. Base excess: a historical review – has the calculation of base excess been standardized the last 20 years ? Clin Chim Acta 2001; 307: 193-95.

- Morgan T. The Stewart approach – One clinician’s perspective. Clin Biochem Review 2009; 30: 41-54.

- Roemer V. The significance of bases excess (BEB) and base excess in the extracellular fluid compartment (BE ecf). www.acutecaretesting.org Jul 2010.

- Juern J, Khatri V, Weigelt J. Base excess: a review. J Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2012; 73: 27-32.

- Toffaletti JG. Blood gases and electrolytes. 2nd ed. Washington DC: AACC press, 2009: 1-39.

- Verma A, Roach P. Interpretation of arterial blood gases. Australian Prescriber 2010: 124-29.

- Higgins C. Clinical aspects of the anion gap. www.acutecaretesting.org Jul 2009.

- Wallach JB. Handbook of interpretation of diagnostic tests. 6th ed. United States of America: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data, 1996.

- Paulson WD, Roberts WL, Lurie AA, Koch DD, Butch AW, Aguanno JJ. Wide variation in serum anion gap measurements by chemistry analyzers. Am J Clin Pathol 1998; 110: 735-42.

- Kraut J, Madias N. Serum anion gap: its uses and limitations in clinical medicine. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 2: 162-74.

- Brandis K. Acid-base physiology: the anion gap. www.anaesthesiamcq.com/AcidBaseBook (Accessed Dec 2012).

- Gabow PA, Kaehny WD, Fennessey PV, Goodman SI, Gross PA, Schrier RW. Diagnostic importance of an increased serum anion gap. N Engl J Med 1980; 303: 854-58.

- Gabow PA. Disorders associated with an altered anion gap. Kidney Int 1985; 27: 472-83.

- Feldman M, Soni N, Dickson B. Influence of hypoalbuminemia or hyperalbuminemia on the serum anion gap. J Clin Lab Med 2005; 146: 317-20.

- Fidkowski C, Helstrom J. Diagnosing metabolic acidosis in the critically ill: bridging the anion gap, Stewart, and base excess methods. Can J Anesth 2009; 56: 247-56.

- Engquist A. Fluids/Electrolytes/Nutrition. 1st ed. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1985.

- Galindo S. Arterial blood gases (ABGs). SOP number CH010, Version 1. 2010; Aug 23. http://www.isu.edu/~galisusa/BloodGasSOP.html (Accessed Jan 2014).

- Miles R, Roberts M, Putnam A et al. Comparison of serum and heparinized plasma samples of measurement of chemistry analytes. Clin Chem 2004; 50: 1704-06.

- Horn J, Hansten P. Hyperkalemia due to drug interactions. Parmacy Times 2004; January: 66-67.

- Firth JD. Disorders of potassium homeostasis. In: Warrel DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, eds. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010: 3831-45.

- Kjeldsen K. Hypokalemia and sudden cardiac death. Exp Clin Cardiol 2010; 15: e96-99.

- Zull DN. Disorders of potassium metabolism. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1989, 7, 4: 771-94.

- Nyirenda M, Tang J, Padfield P, Seckl J. Hyperkalaemia. BMJ 2009; 339: 1019-24.

- Wennecke G. Useful tips to avoid preanalytical errors in blood gas testing: electrolytes. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2003.

- Narins RG. Maxwell and Kleemann’s clinical disorders of fluid and electrolyte metabolism. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

- Evans K, Greenberg A. Hyperkalemia: a review. J Intensive Care Med 2005; 20: 272-90.

- Mandal AK. Hypokalemia and hyperkalemia. Med Clin North Am 1997; 81, 3: 611-39.

- Van den Bosch A, Van der Klooster J, Zuidgeest D et al. Severe hypokalaemic paralysis and rhabdomyolysis due to ingestion of liquorice. Neth J Med 2005; 63: 146-48.

- Stankovic A. Elevated serum potassium values – the role of preanalytic variables. Am J Clin Pathol 2004; 121: S105-11.

- Vendeloo M, Aarnoudse A, van Bommel E. Life-threatening hypokalemic paralysis associated with distal renal tubular acidosis. Netherlands J Medicine 2011; 69: 35-38.

- El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiology Journal 2011; 18: 233-45.

- Liamis G, Milliouis H, Elisaf M. A review of drug-induced hyponatremia. Am J Kid Dis 2008; 52:144-49.

- Douglas I. Hyponatremia: why it matters, how it presents, how we manage it. Cleve Clin J Med 2006; 73: S4-12.

- Palevsky P, Bhagrath R, Greenberg G. Hypernatremia in hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124: 197-203.

- Funk GC, Lindner G, Druml W et al. Incidence and prognosis of dysnatremias present on ICU admission. Intensive Care Medicine 2010; 36: 304-11.

- Lien YH, Shapiro JI. Hyponatremia: Clinical diagnosis and management. Am J Med 2007; 120: 653-58.

- Smith D, Mckenna K, Thompson C. Hyponatraemia. Clin Endocrinol 2000; 52: 667-78.

- Brown I, Tzulaki I, Candais V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38: 791-813.

- Hoorn EJ, Halperin ML, Zietse R. Diagnostics approach to the patient with hyponatremia: traditional versus physiology-based options. Q J Med 2005; 98: 529-40.

- Bhattacharjee D, Page S. Hypernatraemia in adults: a clinical review. Acute Medicine 2010; 9: 60-65.

- Reddy P, Mooradian A. Diagnosis and management of hyponatremia in hospitalized patients. Int J Clin Pract 2009; 63:1494-1508.

- Adrogue H, Madias N. Hypernatremia. New Eng J Med 2000; 342: 1493-99.

- Fortgens P, Pillay T. Pseudohyponatremia revisited – a modern-day pitfall. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2011; 135: 516-19.

- Higgins C. Pseudohyponatremia. www.acutecaretesting.org Jan 2007.

- Tani M, Morimatsu H, Takatsu F et al. The Incidence and prognostic value of hypochloremia in critically ill patients. The Scientific World Journal 2012; 2012: 1-7.

- Becket G, Walker S, Rae P, Asby P. Lecture notes: clinical biochemistry. 8th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- Berend K, Hulsteijn L, Gans R. Chloride: the queen of electrolytes. Eur J Intern Med 2012; 23: 203-11.

- Charles J, Heliman R. Metabolic acidosis. Hospital Physician 2005; March: 37-42.

- Galla J. Metabolic alkalosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11: 369-75.

- Hästbacka J, Pettilä V. Prevalence and predictive value of ionized hypocalcemia among critically ill patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003; 47: 1264-69.

- Lier H, Maegele M. Incidence and significance of reduced ionized calcium in massive transfusion. International Journal of Intensive Care 2012; 77-80.

- Ramasamy I. Recent advances in physiological calcium homeostasis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2006; 44: 237-73.

- Marshall W, Bangert S, Lapsley M. Calcium phosphate and magnesium. In: Clinical chemistry. 7th ed. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2012.

- Higgins C. Ionized calcium. www.acutecaretesting.org Jul 2007.

- Ho KM, Leonard AD. Concentration-dependent effect of hypocalcaemia on mortality of patients with critical bleeding requiring massive transfusion: a cohort-study. Anaesth Intensive care 2011; 39: 46-54.

- Cooper M, Gittoes N. Diagnosis and management of hypocalcemia. BMJ 2008; 336: 1298-302.

- Assadi F. Hypercalcemia – an evidence-based approach to clinical cases. Iranian J Kidney Disease 2009; 3: 71-79.

- Atkinson MA, Maclaren NK. The pathogenesis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Eng J Med 1994; 331: 1428-36.

- Mulligan, M. Hyperglycemic control in the ICU. www.acutecaretesting.org Apr 2010.

- Rozance PJ, Hay Jr WW. Describing hypoglycemia – definition or operational threshold. Early Hum Dev 2010; 86: 275-80.

- Young JW. Gluconeogenesis in cattle: significance and methodology. J Dairy Sci 1977; 60: 1-15.

- Vander AJ, Sherman JH, Luciano DS. Human physiology: the mechanisms of body function. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1990.

- Biswajit S. Post prandial plasma glucose level less than the fasting level in otherwise healthy individuals during routine screenings. Indian J Clin Biochem 2006; 21, 2: 67-71.

- Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2001; 345,19: 1359-67.

- American Diabetes Association (ADA). Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35, Suppl 1: S11-S63.

- Fahy BG, Sheehy AM, Coursin DB. Glucose control in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 1769-76.

- Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 449-61.

- Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94,3: 709-28.

- Eggert L. Guidelines for management of neonatal hypoglycemia. Intermountain healthcare. Patient and provider publications 801.442.2963 CPM011, 2012; 1-2.

- Fernández BA, Pérez IC. Neonatal hypoglycemia – current concepts. In: Rigobelo E, ed. Hypoglycemia – causes and occurrences. InTech, 2011. http://www.intechopen.com/books/hypoglycemia-causes-and-occurrences/neonatalhypoglycemia-current-concepts (Accessed Feb 2013).

- Fugelseth D. Neonatal hypoglycemia. Dsskr Nor Laegeforen 2001; 121,14: 1713-16.

- Chan SW. Neonatal hypoglycemia. Up to date reviews 2011. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/neonatal-hypoglycemia (Accessed Mar 2013).

- Hawdon JM. Glucose and lactate in neonatology (clinical focus). www.acutecaretesting.org Jun 2002.

- Halamek LP, Stevenson DK. Neonatal hypoglycemia, part II: pathophysiology and therapy. Clin Pediatr 1998; 37: 11-16.

- Robergs RA, Ghiasvand F, Parker D. Biochemistry of exercise-induced metabolic acidosis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2004; 287: R502-16.

- Shirey TL. POC lactate: A marker for diagnosis, prognosis, and guiding therapy in the critically ill. Point of Care 2007; 6: 6192-200.

- Mordes JP, Rossini AA. Lactic acidosis. In: Irwin R, Cera FB, Rippe JM, eds. Irwin and Rippe’s intensive care medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1999.

- Yudkin J, Cohen RD. The contribution of the kidney to the removal of lactic acid load under normal and acidotic conditions in the conscious rat. Clin Sci Mol Med 1975; 48: 121-31.

- Higgins C. L-lactate and D-lactate – clinical significance of the difference. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2011.

- Uribarri J, Oh MS, Carroll HJ. D-lactic acidosis. A review of clinical presentation, biochemical features, and pathophysiologic mechanisms. Medicine 1998; 77: 73-82.

- Mizock B. Controversies in lactic acidosis: implications in critically ill patients. JAMA 1987; 258: 497-501.

- Casaletto J. Differential diagnosis of metabolic acidosis. Emerg Med Clin N Amer 2005; 23: 771-87.

- Essex DW, Jun DK, Bradley TP. Lactic acidosis secondary to severe anemia in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Am J Hematol 1998; 55: 110-11.

- Aberman A, Hew E. Lactic acidosis presenting as acute respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978; 118: 961-63.

- Foster M, Goodwin SR, Williams C, Loeffler J. Recurrent life-threatening events and lactic acidosis caused by chronic carbon monoxide poisoning in an infant. Pediatrics 1999; 104: e34-35.

- Freidenburg AS, Brandoff DE, Schiffman FJ. Type B lactic acidosis as a severe metabolic complication in lymphoma and leukemia: a case series from a single institution and literature review. Medicine, 2007; 86: 225-32.

- John M, Moore CB, James IR et al. Chronic hyperlactatemia in HIV-infected patients taking antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2001; 15: 717-23.

- Bonnet F, Bonarek M, Abridj A et al. Severe lactic acidosis in HIV-infected patients treated by nucleoside reverse-transcriptase analogs: a report of 9 cases. Rev Med Interne 2003; 24: 11-16.

- Farrell DF, Clark AF, Scott CR, Wennberg RP. Absence of pyruvate decarboxylase in man: A cause of congenital lactic acidosis. Science 1975; 187: 1082-84.

- Rallison ML, Meikle AW, Zigrang WD. Hypoglycemia and lactic acidosis associated with fructose-1,6 diphosphatase deficiency. J Pediatrics 1979; 94: 933-36.

- Bianco-Barca O, Gomez-Lado C, Rodrige-Saez E et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficit associated to the C515T mutation in exon 6 of the E1alpha gene. Rev Neurol 2006; 43: 341-45.

- Shapiro NI, Howell MD, Talmor D et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in emergency department patients with infection. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 45: 524-28.

- Trzeciak S, Dellinger RP, Chansky ME et al. Serum lactate as a predictor of mortality in patients with infection. Intens Care Med 2007; 33: 970-77.

- Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Bakker J. Blood lactate monitoring in critically ill patients: a systematic health technology assessment. Crit Care Med 2009; 37: 2827-39.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013; 41: 580-637.

- American Academy of Paediatrics. Subcommittee of Hyperbilirubinemia. Clinical practice guideline: management of hyperbilirubinemia in newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 2004; 114: 296-316.

- Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier health science, 2007.

- Maisels MJ. Neonatal jaundice. Pediatr Rev 2006; 27: 443-54.

- Bancroft JD, Kreamer B, Gourlev GR. Gilbert syndrome accelerates development of neonatal jaundice. J Pediatr 1998; 32,4: 656-60.

- Herrine SK. Jaundice. The Merck manuals online medical library for healthcare professionals. 2009. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/search.html?qt=jaundice&start=1&context=%2Fprofessional (Accessed May 2013).

- Maisels MJ, McDonagh AF. Phototherapy for neonatal jaundice. N Engl Med 2008; 358,9: 920-28.

- Maisels MJ, Watchko J. Treatment of jaundice in low birth weight infants. Arch Dis Child fetal neonatal Ed 2003; 88: F459-63.

- Myers GL, Miller WG, Coresh J et al. Recommendations for improving serum creatinine measurement: a report from the laboratory working group of the National Kidney Disease Education Program (NKDEP). Clin Chem 2006; 52: 5-18.

- US recommendations. National Kidney Disease Education Program (NKDEP).www.nkdep.nih.gov, (Accessed Jan 2013).

- Preiss DJ, Godber IM, Lamb EJ, Dalton RN, Gunn IR. The influence of a cooked meat meal on estimated glomerular filtration rate. Ann Clin Biochem 2007; 44: 35-42.

- Valtin H. Renal dysfunction: mechanisms involved in fluid and solute imbalance. Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1979.

- Miller BF, Winkler AW. The renal excretion of endogenous creatinine in man: comparison with exogenous creatinine and inulin. J Clin Invest, 1938; 17; 31-40.

- Higgins C. Creatinine measurement in the radiology department 1. www.acutecaretesting.org Apr 2010.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003475.htm (Accessed Jan 2013).

- Kellum JA, Aspelin P, Barsoum RS et al. KDIGO. Clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney International Supplements 2012; 2: 19-36.

- Bagshaw SM, George C, Bellomo R, ANZICS Database Management Committee. Early acute kidney injury and sepsis: a multicentre evaluation. Crit Care 2008; 12,2: R47.

- Hoste EAJ, Clermont G, Kersten A et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care 2006; 10: R73.

- Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicentre study. JAMA 2005; 17,294: 813-18.

- Pannu N, Nadim MK. An overview of drug-induced acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 2008; 36: S216-23.

- Bentley ML, Corwin HL, Dasta J. Drug-induced acute kidney injury in the critically ill adult: recognition and prevention strategies. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: S169-74.

- Vanholder R, Massy Z, Argiles A et al. Chronic kidney disease as cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20: 1048-56.

- Levey AS, Eckardt K, Tsukamoto Y et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO). Kidney International 2005; 67: 2089-100.

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Bolton K et al. National Kidney Foundation. Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease evaluation classification and stratification. Am J kidney Dis 2002; 39: S1-266. http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/pdf/ckd_evaluation_classification_stratification.pdf

- Higgins C. Creatinine measurement in the radiology department 2. www.acutecaretesting.org Oct 2010.

- Cronin R. Contrast induced nephropathy: pathogenesis and prevention. Pediatr Nephrol 2010; 25: 191-204.

- Schweiger MJ, Chambers CE, Davidson CJ. Prevention of contrast induced neophropathy: Recommendations for high risk patient undergoing cardiovascular procedures. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2007; 69: 135-40.

- Levey A, Bosch J, Lewis J et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new predictive equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study group. Ann Intern Med 1999; 130: 461-70.

- Lamb EJ, Tomson CR, Roderick PJ et al. Estimating kidney function in adults using formulae. Ann Clin Biochem 2005; 42: 321-45.

- National Kidney Disease Education Program (NKDEP). http://nkdep.nih.gov/lab-evaluation/gfr-calculators.shtml. (Accessed Jan 2013).

- Schwartz GJ, Work DF. Measurement and estimation of GRF in children and adolescents. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4: 1832-43.

- National kidney foundation. http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator.cfm (Accessed Feb 2013).

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150,9: 604-12.

- Peruzzi WT. Setting the record on shunt. www-acutecaretesting.org 2004.

- Wandrup JH. Quantifying pulmonary oxygen transper deficits in critically ill patients, Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995; 39: 2744.

- Jardins TD, Burton GG. Clinical manifestations and assessment of respiratory disease. 6st edition. Mosby Elsevier 2011.

- Newby LK, Jesse RL, Babb JD et al. ACCF 2012 Expert consensus document on practical clinical considerations in the interpretation of troponin elevations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 2427-63.

- Christenson R, Azzazy H. Biochemical markers of the acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chem 1998; 44: 1855-64.

- Korff S, Katus HA, Giannitsis E. Differential diagnosis of elevated troponins. Heart 2006; 92: 987-93.

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2551-67.

- Daubert MA, Jeremias A. The utility of troponin measurement to detect myocardial infarction: review of the current findings. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2010; 6: 691-99.

- Apple F. A new season for cardiac troponin assays: it’s time to keep a scorecard. Clin Chem 2009; 55: 1303-06.

- Hamm C, Bassand JP, Agewall S et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 2999-3054.

- Steg PG, James SK, Atar D et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 2569-619.

- Kurz K, Schild C, Isfort P, Katus HA, Giannitsis E. Serial and single time-point measurement of cardiac troponin T for prediction of clinical outcomes in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Res Cardiol 2009; 98: 94-100.

- Bruyninckx R, Aertgeerts B, Bruyninckx P, Buntinx F. Signs and symptoms in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2008; 58: 105-11.

- Kirchberger I, Heier M, Kuch B, Wende R, Meisinger C. Sex differences in patient-reported symptoms associated with myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107: 1585-89.

- Apple F, Ler R, Murakami M. Determination of 19 cardiac troponin I and T assay 99th percentile values from a common presumably healthy population. Clin Chem 2012; 58: 1574-81.

- Giannitsis E, Kurz K, Hallermayer K, Jarausch J, Jaffe AS, Katus HA. Analytical validation of a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T assay. Clin Chem 2010; 56: 254-61.

- Saenger A, Beyrau R, Braun S et al. Multicenter analytical evaluation of a high- sensitivity troponin T assay. Clin Chim Acta 2011; 412: 748-54.

- Jardine RM, Dalby AJ, Klug EG et al. Consensus statement on the use of high sensitivity cardiac troponins. SAHeart 2012; 9: 210-15.

- Agewall S, Giannitsis E, Jernberg T, Katus HA. Troponin elevation in coronary vs. non-coronary disease. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 404-11.

- McClean AS, Huang SJ. Cardiac biomarkers in the intensive care unit. Ann Intensive Care 2012; 2: 1-11.

- Clerico A, Fontana M, Zyw L, Passino C, Emdin M. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and the N-terminal part of the propeptide of BNP immunoassays in chronic and acute heart failure: a systematic review. Clin Chem 2007; 53: 813-22.

- Yeo KT, Wu AH, Apple FS et al. Multicenter evaluation of the Roche NT-proBNP assay and comparison to the Biosite Triage BNP assay. Clin Chim Acta 2003; 338: 107-15.

- Hall C. Essential biochemistry and physiology of (NT-pro) BNP. Eur J Heart Fail 2004; 6: 257-60.

- Kuwahara K, Nakao K. Regulation and significance of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides as cardiac homones. Endocr J 2010; 57: 555-65.

- La Villa G, Stefani L, Lazzeri C et al. Acute effects of physiological increments of brain natriuretic peptide in humans. Hypertension 1995; 26: 628-33.

- Mair J. Biochemistry of B-type natriuretic peptide – where are we now ? Clin Chem Lab Med 2008; 46: 1507-14.

- Nishikimi T, Maeda N, Matsuoka H. The role of natriuretic peptides in cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res 2006; 69: 318-28.

- Kim H-N, Januzzi JL. Natriuretic peptide testing in heart failure. Circulation 2011; 123: 2015-19.

- DeFilippi, van Kimmenade RR, Pinto YM. Amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide testing in renal disease. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101: 82-88.

- Apple FS, Wu HA, Jaffe AS et al. National academy of clinical biochemistry and IFCC committee for standardization of markers of cardiac damage laboratory medicine practice guidelines: Analytical issues for biomarkers of heart failure. Circulation 2007; 116: e95-98.

- Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Burnett JC. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: impact of age and gender. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40: 976-82.

- Galasko GI, Lahiri A, Barnes SC, Collinson P, Senior R. What is the normal range for N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide ? How well does this normal range screen for cardiovascular disease ? Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 2269-76.

- Nir A, Lindinger A, Rauh M et al. NT-pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in infants and children: reference values based on combined data from four studies. Pediatr Cardiol 2009; 30: 3-8.

- McMurray J, Adamopoulus S, Anker S et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1787-847.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic heart failure: the management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE CG108 2010. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG108/Guidance/pdf/English

- Cowie MR, Collinson PO, Dargie H et al. Recommendations on the clinical use of B-type natriuretic peptide testing (BNP or NTproBNP) in the UK and Ireland. Br J Cardiol 2010; 17: 76-80.

- Mozid AM, Papadopoulou SA, Skippen A, Khokhar AA. Audit of the NT-ProBNP guided transthoracic echogardiogram service in Southend. Br J Cardiol 2011; 18: 189-92.

- Zkynthinos E, Kiropoulos T, Gourgoulianis K, Filippatos G. Diagnostic and prognostic impact of brain natriuretic peptide in cardiac and non-cardiac diseases. Heart Lung 2008; 37: 275-85.

- Freitag MH, Larson MG, Levy D et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels and blood pressure tracking in the Framingham heart study. Hypertension 2003; 41: 978-83.

- Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Sabatine MS et al. Evaluation of B-type natriuretic peptide for risk assessment in unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: B-type natriurectic peptide and prognosis in TACTICS-TIMI 18. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41: 1264-72.

- Asselbergs FW, van den Berg MP, Bakker SJ et al. N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide levels predict newly detected atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. Neth Heart J 2008; 16: 73-78.

- Lega JC, Lacasse Y, Lakhal L, Provencher S. Natriuretic peptides and troponins in pulmonary embolism. Thorax 2009; 64: 869-75.

- Bozkanet E, Tozkoparan E, Baysan O, Deniz O, Ciftci F, Yokusoglu M. The significance of elevated brain natriuretic peptide levels in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Int Med Res 2005; 33: 537- 44.

- Tagore R, Ling LH, Yang H, Daw H-Y, Chan Y-H, Sethi SK. Natriuretic peptides in chronic kidney disease. CJASN 2008; 3: 1644-61.

- Varpula M, Pulkki K, Karlsson S, Roukonen E, Pettilä V, FINNSEPSIS Study Group. Predictive value of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 1277-83.

- Desai AS, Ribbins-Domingo K, Shilipak MG, Wu AH, Ali S, Whooley MA. Association between anaemia and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP): findings from the heart and soul study. Eur J Heart Fail 2007; 9: 886-91.

- Januzzi JL, van Kimmenade R, Lainchbury J et al. NT-proBNP testing for diagnosis and short-term prognosis in acute destabilized heart failure: an international pooled analysis of 1256 patients: the international collaborative of NT-proBNP study. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 330-37.

- Maisel A, Mueller C, Adams K et al. State of the art: using natriuretic peptide levels in clinical practice. Eur J Heart Fail 2008; 10: 824-39.

- Maisel AS, Krishnaswamy P, Nowak RM et al. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. New Eng J Med 2002; 347: 161-67.

- Masson S, Latini R, Anand IS et al. Direct comparison of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and amino-terminal proBNP in a large population of patients with chronic and symptomatic heart failure: The valsartan heart failure (Val-HeFT) data. Clin Chem 2006; 52: 1528-38.

- Richards AM, Troughton RW. The use of natriuretic peptides to guide and monitor heart failure therapy. Clin Chem 2012; 58: 62-71.

- Jourdain P, Jondeau G, Funck F et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide-guided therapy to improve outcome in heart failure: the STARS-BNP multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 24: 1733-39.

- Januzzi JL, Rehman SU, Mohammed AA et al. Use of amino-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide to guide outpatient therapy of patients with chronic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 1881-89.

- Martinez-Rumayor A, Richards AM, Burnett JC, Januzzi JL. Biology of the natriuretic peptides. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101: 3-8.

- Mehra MR, Maisel A. B-type natriuretic peptide in heart failure: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic use. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2005; 4: 10-20.

- Gailani D, Renné T. Intrinsic pathway of coagulation and arterial thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007; 27: 2507-13.

- Adam SS, Key NS, Greenberg CS. D-dimer antigen: current concepts and future prospects. Blood 2009; 113: 2878-87.

- Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet 2012; 379: 1835-46.

- Galanaud JP, Quenet S, Rivron-Guillot K et al. Comparison of the clinical history of symptomatic isolated distal deep-vein thrombosis vs. proximal deep vein thrombosis in 11086 patients. J Thromb Haemost 2009; 7: 2028-34.

- Takach Lapner S, Kearon C. Diagnosis and management of pulmonary embolism. BMJ 2013; 346: f757.

- Chopra N, Doddamreddy P, Grewal H, Kumar PC. An elevated D-dimer value: a burden on our patients and hospitals. Int J Gen Med 2012; 5: 87-92.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolic diseases: the management of venous thromboembolic diseases and the role of thrombophilia testing. NICE CG144 2012. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellences. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg144

- Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1227-35.

- Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135: 98-107.

- Cosmi B, Legnani C, Tosetto A et al. Usefulness of repeated D-dimer testing after stopping anticoagulation for a first episode of unprovoked venous thromboembolism: the PROLONG II prospective study. Blood 2010; 115: 481-88.

- Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, Watson HG. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol 2009; 145: 24-33.

- Shimony A, Filion KB, Mottillo S, Dourian T, Eisenberg MJ. Meta-analysis of usefulness of D-dimer to diagnose acute aortic dissection. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107: 1227-34.

- Bauersachs RM. Clinical presentation of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2012; 25: 243-51.

- Tripodi A. D-dimer testing in laboratory practice. Clin Chem 2011; 57: 1256-62.

- Raby A. D-dimer assay issues and standardization: QMP-LS studies. Conference: Mayo/NASCOLA coagulation testing quality conference april 17th, 2009.

- Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Pennells L, et al. C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and cardiovascular disease prediction. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1310-20.

- Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 1805–12. Correction in: J Clin Invest. 2003; 112, 2: 299.

- Gruys E, Toussaint MJ, Niewold TA, Koopmans SJ. Acute phase reaction and acute phase proteins. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2005; 6: 1045-56.

- Casas JP, Shah T, Hingorani AD, Danesh J, Pepys MB. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Intern Med 2008; 264: 295-314.

- Reeves G. C-reactive protein. Aust Prescr 2007; 30: 74-76.

- Kushner I, Rzewnicki D, Samols D. What does minor elevation of C-reactive protein signify ? Am J Med 2006; 119: 166.e17-28.

- Allin KH, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated C-reactive protein in the diagnosis, prognosis, and cause of cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2011; 48: 155-70.

- Heikkilä K, Ebrahim S, Lawlor DA. A systematic review of the association between circulating concentrations of C reactive protein and cancer. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007; 61: 824-33.

- Pepys M. The acute phase response and C-reactive protein. In: Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, eds. Oxford textbook of medicine.5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010: 1752-59.

- McCabe RE, Remington JS. C-reactive protein in patients with bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol 1984; 20: 317-19.

- Hofer N, Zacharias E, Müller W, Resch B. An update on the use of C-reactive protein in early-onset neonatal sepsis: current insights and new tasks. Neonatology2012; 102: 25-36.

- Grønn M, Slørdahl SH, Skrede S, Lie SO. C-reactive protein as an indicator of infection in the immunosuppressed child. Eur J Pediatr 1986; 145: 18-21.

- Platt JJ, Ramanathan ML, Crosbie RA et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of postoperative infective complications after curative resection in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 4168-77.

- Hautemanière A, Florentin A, Hunter PR, Bresler L, Hartemann P. Screening for surgical nosocomial infections by crossing databases. J Infect Public Health 2013; 6: 89-97.

- Manzano S, Bailey B, Gervaix A, Cousineau J, Delvin E, Girodias JB. Markers for bacterial infection in children with fever without source. Arch Dis Child 2011; 96: 440-46.

- Bilavsky E, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Ashkenazi S, Amir J. C-reactive protein as a marker of serious bacterial infections in hospitalized febrile infants. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98: 1776-80.

- De Cauwer HG, Eykens L, Hellinckx J, Mortelmans LJ. Differential diagnosis between viral and bacterial meningitis in children. Eur J Emerg Med 2007; 14: 343-47.

- McGowan DR, Sims HM, Zia K, Uheba M, Shaikh IA. The value of biochemical markers in predicting a perforation in acute appendicitis. ANZ J Surg 2013; 83: 79-83.

- Devran O, Karakurt Z, Adıgüzel N et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of mortality in patients affected with severe sepsis in intensive care unit. Multidiscip Respir Med 2012; 7: 47.

- Nseir W, Farah R, Mograbi J, Makhoul N. Impact of serum C-reactive protein measurements in the first 2 days on the 30-day mortality in hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia: a cohort study. J Crit Care 2013; 28: 291-95.

- Haran JP, Beaudoin FL, Suner S, Lu S. C-reactive protein as predictor of bacterial infection among patients with an influenza-like illness. Am J Emerg Med 2013; 31: 137-44.

- Cals JW, Schot MJ, de Jong SA, Dinant GJ, Hopstaken RM. Point-of-care C-reactive protein testing and antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2010; 8: 124-33.

- Póvoa P, Salluh JI. Biomarker-guided antibiotic therapy in adult critically ill patients: a critical review. Ann Intensive Care 2012; 2: 32.

- Otterness IG. The value of C-reactive protein measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1994; 24: 91-104.

- Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Laboratory markers in IBD: useful, magic, or unnecessary toys ? Gut 2006; 55: 426-31.

- Mazlam MZ, Hodgson HJ. Why measure C reactive protein ? Gut 1994; 35: 5-7.

- Leeb BF, Bird HA. A disease activity score for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 1279-83.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Antenatal Care: routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. NICE CG62 2008. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellences. Available from: http://nice.org.uk/CG062

- Montagnana M, Trenti T, Aloe R, Cervellin G, Lippi G. Human chorionic gonadotropin in pregnancy diagnostics. Clin Chim Acta 2011; 412: 1515-20.

- Cole LA. hCG, the wonder of today’s science. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012; 10: 24.

- Cole LA, DuToit S, Higgins TN. Total hCG tests. Clin Chim Acta 2011; 412: 2216-22.

- Muller CY, Cole LA. The quagmire of hCG and hCG testing in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol 2009; 112: 663-72.

- Stenman UH, Tiitinen A, Alfthan H, Valmu L. The classification, functions and clinical use of different isoforms of HCG. Hum Reprod Update 2006; 12: 769-84.

- Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1796-99.

- Cole LA. New discoveries on the biology and detection of human chorionic gonadotropin. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2009; 7: 8.

- Cole LA. Biological functions of hCG and hCG-related molecules. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2010; 8: 102.

- Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE. Clinical chemistry of pregnancy. In: Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE, eds. Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. 4th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders, 2006: 2153-206.

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988; 319: 189-94.

- Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PF, Zhou L, Hummel AC, Guo W. Symptomatic patients with an early viable intrauterine pregnancy: HCG curves redefined. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104: 50-55.

- Poikkeus P, Hiilesmaa V, Tiitinen A. Serum HCG 12 days after embryo transfer in predicting pregnancy outcome. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 1901-05.

- Deutchman M, Tubay AT, Turok D. First trimester bleeding. Am Fam Physician 2009; 79: 985-94.

- Seeber BE. What serial hCG can tell you, and cannot tell you, about an early pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2012; 98: 1074-77.

- Barnhart KT. Clinical practice. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 379-87.

- Yoo A Zacarro J. Falsely low serum hCG level in a patient with hydatidiform mole caused by the “High-Dose Hook Effect”. Laboratory Medicine 2000; 31: 431-35.

- Malin GL et al. Strength of association between umbilical cord pH and perinatal and long term outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010; 340:c1471.

- Olsen TG, Barnes AA, King JA. Elevated HCG outside of pregnancy – diagnostic considerations and laboratory evaluation. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2007; 62: 669-74.

Cookies are used on this website

Use of cookiesPlease enter a valid email

We will be sending an e-mail invitation to you shortly to sign in using Microsoft Azure AD.

It seems that your e-mail is not registered with us

Please click "Get started" in the e-mail to complete the registration process

Radiometer is using Microsoft AZURE Active Directory to authenticate users

Radiometer uses Azure AD to provide our customers and partners secure access to documents, resources, and other services on our customer portal.

If your organization is already using Azure AD you can use the same credentials to access Radiometer's customer portal.

Key benefits

- Allow the use of existing Active Directory credentials

- Single-sign on experience

- Use same credentials to access future services

Request access

You will receive an invitation to access our services via e-mail when your request has been approved.

When you accept the invitation, and your organization is already using AZURE AD, you can use the same credentials to access Radiometer's customer portal. Otherwise, a one-time password will be sent via e-mail to sign in.